Abstract

This post details a Proof of Concept (PoC) project I originally developed back in 2021. It represents one of my earliest explorations into the complex worlds of Windows Internals and kernel development.

The only objective of this project was my own education and technical curiosity. The techniques discussed (such as bypassing memory protections and hooking system drivers) are documented here strictly for academic and research purposes. I do not, in any way, encourage or condone the use of these methods to compromise software integrity or for any malicious activity. This is simply a technical look back at a foundational learning project.

1. Introduction: My Journey into the Windows Kernel

Since my first steps in programming, I’ve always been fascinated by the “magic” that happens under the hood. How does the operating system really work? How do software and hardware interact? This curiosity led me down a path that, inevitably, ended in the Windows Kernel.

Today, I want to share what was one of my most challenging and educational personal projects back when I started learning about Windows Internals: a kernel-mode driver designed to intercept a specific function within a legitimate Microsoft driver (win32kbase.sys) using an advanced technique known as Data Pointer Hooking. This project, developed for purely educational purposes, was a deep dive into Windows Internals.

2. The Kernel World: User-Mode vs. Kernel-Mode

To understand this project, we must first grasp the fundamental duality of Windows:

- User-Mode: This is where all our everyday applications live (browsers, text editors, games). It’s a safe, isolated environment. If an application crashes, the OS can terminate it without compromising global stability.

- Kernel-Mode: This is the core of the operating system. It’s where critical components like the memory manager, process scheduler, and—crucially—drivers reside. A driver is software that allows the kernel to interact with hardware (graphics card, keyboard, network) and with critical system functions. If something goes wrong here, get ready for a Blue Screen of Death (BSOD)!

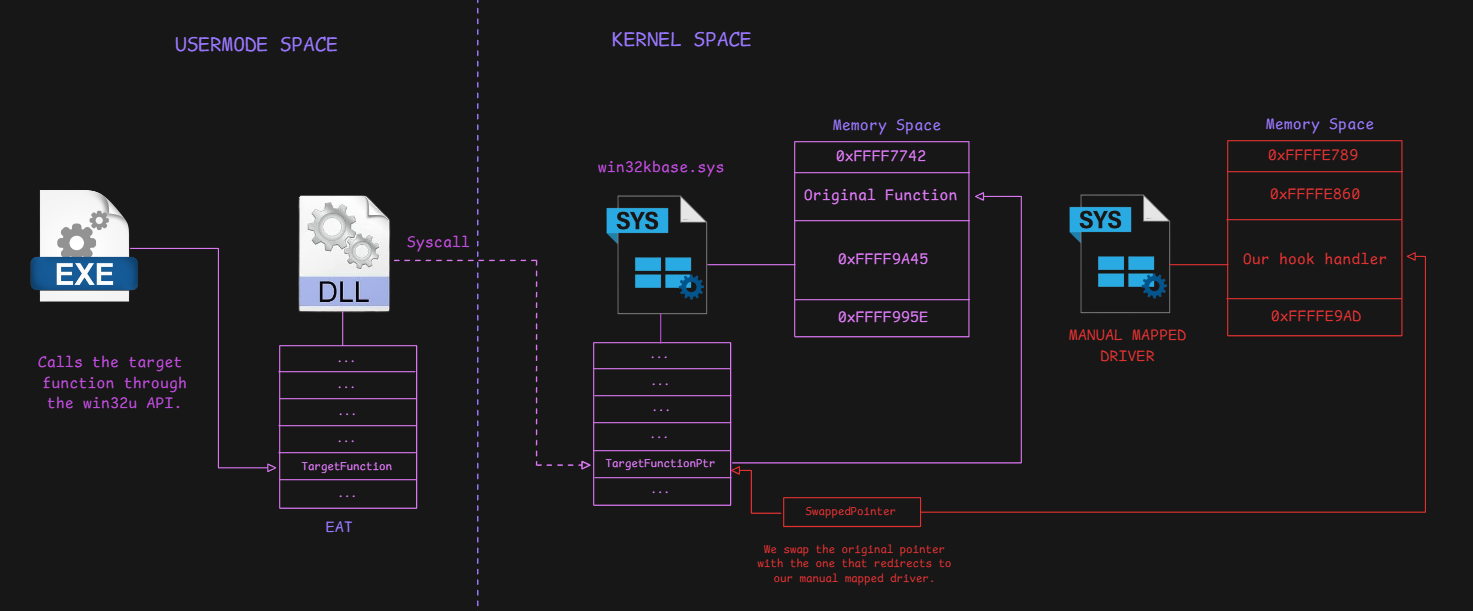

2.1. Tracing the Call Flow to Our Hook

So, how does a simple click in a User-Mode application get handled by a driver we want to hook? It follows a precise path designed to safely cross that User-Mode/Kernel-Mode boundary.

Let’s trace the journey:

- User-Mode Application: Your code calls a function from a system API, like the Win32 API (e.g., in

user32.dllorgdi32.dll). - System DLL Wrapper: These high-level functions often call lower-level functions exported by DLLs like

win32u.dllorntdll.dll. The function you’re calling, which is listed in the DLL’s Export Address Table (EAT), is frequently just a small “stub” or wrapper. - The

syscall: This wrapper’s main job is to prepare the arguments (placing them in the correct registers) and then execute asyscallinstruction. This instruction is the magic gate—it intentionally triggers a transition from the unprivileged User-Mode (Ring 3) to the privileged Kernel-Mode (Ring 0). - Kernel-Mode Dispatcher: The CPU hands control to the kernel’s central

syscalldispatcher. This dispatcher checks thesyscallnumber (an ID for the requested function) and routes the request to the correct kernel module to handle it. - Target Driver (

win32kbase.sys): For many GUI and graphics-related syscalls, the handler iswin32kbase.sys. The kernel passes the request to this driver. - The Hooked Pointer: This is where our project comes in. As

win32kbase.sysprocesses the request, it will, at some point, call one of its internal helper functions by referencing a function pointer stored in its.datasection.

Because we’ve already hijacked that pointer, the driver thinks it’s calling its own legitimate function, but it’s actually calling our hook handler, giving us control of the execution flow.

3. The Role of win32kbase.sys

Choosing win32kbase.sys as a target was no accident. This driver is an essential part of the Windows graphics subsystem. It handles critical functions related to the Graphical User Interface (GUI), such as window management, rendering, user input, and more.

It’s an interesting target because its functions are constantly invoked by User-Mode applications, making it an ideal point to intercept certain low-level operations.

4. Types of Hooking in Windows

The interception of functions is known as hooking. Several techniques exist, each with its pros and cons:

- Inline Hooking (

.textsection): Directly modifies the binary code of a function (in the.textsection) to jump to our code. It’s powerful but more complex to implement and potentially unstable. - IRP Hooking (Dispatch Tables): Intercepts the I/O Request Packets (IRPs) that drivers use to communicate. This is a more “official” way to intercept requests, but it only works for drivers that process IRPs.

- SSDT (System Service Descriptor Table) Hooking: A more complex technique for intercepting system calls (

syscalls). - Data Pointer Hooking (Our Approach): Our method, which focuses on modifying function pointers stored in a driver’s data sections.

5. The Technique: Data Pointer Hooking

My project centers on this last technique. Instead of modifying code (.text) or dispatch tables (IRP), we seek out a function pointer that the target driver (win32kbase.sys) uses internally and redirect it to our own function.

5.1. What is the .data section?

Every executable module (like a driver) is divided into memory sections. The .data section (or .rdata for read-only data) contains global variables, static data, and often, function pointers that the module itself uses. It’s like the driver’s internal address book.

5.2. Locating the Pointer

The first challenge is finding the exact pointer we want to hijack. This involves:

- Loading the target driver: Ensuring

win32kbase.sysis loaded into memory. - Scanning its sections: Iterating through the

.dataor.rdatasections ofwin32kbase.sys. - Identifying the pattern: Searching for a pattern (

signature scanning) that identifies the location of the desired function pointer. In a PoC project, this might be a hardcoded offset if the driver version is known.

NTSTATUS HookCtx::Init( )

{

// Retrieving the base address of the target driver

HookCtx::driver_module = Utils::RetrieveModuleBase( xor_string( "\\SystemRoot\\System32\\win32kbase.sys" ) );

if ( HookCtx::driver_module )

{

// Find the .data pointer by signature scanning

HookCtx::data_pointer = Utils::FindPatternImage( ( PCHAR )HookCtx::driver_module, ( PCHAR )xor_string( "\x8B\x8C\x24\xA8\x00\x00\x00\x44\x8B\xCF" ), ( PCHAR )xor_string( "xxxx???xxx" ) );

if ( HookCtx::data_pointer )

{

...

}

}

...

}5.3. Bypassing Memory Protection (WP Bit)

As mentioned before, a crucial distinction in memory hooking is where you are writing. By convention, a module’s sections are marked with specific permissions:

.datasection: Contains global and staticwritablevariables. This section is marked as Read/Write..rdatasection: Containsread-onlydata (constants, strings). This section is marked as Read-Only to prevent modification..textsection: Contains the executable code. It is marked as Read/Execute.

The CPU enforces these permissions. Even in kernel-mode (Ring 0), the Write Protect (WP) bit in the CR0 register prevents the kernel from writing to pages marked as read-only.

In this PoC the target function pointer resides in the .data section of the legit driver, therefore we do not need to disable the Write Protect bit.

However, if your target pointer was in a read-only section (like .rdata), you would have to bypass this protection. This is achieved by manipulating the processor’s CR0 register, specifically the WP (Write Protect) bit. Disabling it temporarily allows us to write to read-only memory.

Manipulating the CR0 register is an extremely dangerous operation in kernel-mode and can lead to system instability if not handled with extreme care and for very short periods.

// Disable interrupts to ensure atomicity

_disable();

// Read current CR0 register

auto cr0 = __readcr0();

const auto old_cr0 = cr0;

// Clear the Write Protect bit (bit 16)

cr0 &= ~(1UL << 16);

// Write the modified value back to CR0

__writecr0(cr0);

// At this point, kernel write protection is disabled.

// The write to a read-only section would happen here.

// Restore the original CR0 value to re-enable protection

__writecr0(old_cr0);

// Re-enable interrupts

_enable();5.4. The Atomic Swap

Once we have located the pointer, and disabled write protection if needed, the final step is the “swap.” We replace the original pointer with the address of our hook function. It’s crucial that this swap is atomic (indivisible) to prevent race conditions on multi-core systems.

// ...

if ( HookCtx::data_pointer )

{

if ( xor_import(MmIsAddressValid)( HookCtx::data_pointer ) )

{

// Resolve the relative virtual address (RVA) of the pointer

HookCtx::pointer_reference = ( UINT64 )( HookCtx::data_pointer ) - xor_number( 0xC );

HookCtx::pointer_reference = ( UINT64 )HookCtx::pointer_reference + *( PINT )( ( PBYTE )HookCtx::pointer_reference + xor_number( 3 ) ) + xor_number( 7 );

// Swap the target pointer

*( PVOID* )&HookCtx::original_pointer = _InterlockedExchangePointer( ( PVOID* )HookCtx::pointer_reference, ( PVOID )HookCtx::hooked_pointer );

return xor_number( STATUS_SUCCESS );

}

}

// ...6. Design: A “Shellcode-like” Driver

A crucial detail of this project is that it is not a traditional WDM (Windows Driver Model) driver. Instead of being loaded by the Windows driver manager (NtLoadDriver), it is designed to be manually mapped into the kernel’s address space by an external component (e.g., a kernel manual mapping tool).

This implies several fundamental differences:

- No classic

DriverEntry: It lacks the standardDriverEntryfunction and does not receive aPDRIVER_OBJECT. - No

DriverUnload: It does not handle its own unloading or resource cleanup natively. This responsibility falls to the component that maps it. - Position-Independent (PIC): Ideally, the code should be Position-Independent Code (PIC) to run from any memory address.

This design makes it more akin to a kernel “payload” or “shellcode,” which is a common technique in the security and anti-cheat fields.

7. Implementation: Key Concepts

Let’s imagine OriginalTargetFunction is the one whose pointer is in the .data section. Our goal is that when the legitimate driver calls it, it actually calls our hook handler (in this case HookCtx::hooked_pointer).

INT64 __fastcall HookCtx::hooked_pointer( PVOID arg1, PVOID arg2, PVOID arg3, PVOID arg4, DWORD arg5, PVOID arg6, PVOID arg7, DWORD arg8 )

{

// Ensure the caller is in User-Mode, if not, call the original function

if ( Utils::_ExGetPreviousMode( ) != xor_number( UserMode ) )

return HookCtx::original_pointer( arg1, arg2, arg3, arg4, arg5, arg6, arg7, arg8 );

// Ensure the request comes from our user-mode module by checking the size of

// the packet and validating the SECRET_KEY, if not, call the original function

Communication Request = { };

if ( !Utils::ReadVirtualMemory( &Request, arg6, sizeof( Communication ) ) || Request.Reason != SECRET_KEY )

return HookCtx::original_pointer( arg1, arg2, arg3, arg4, arg5, arg6, arg7, arg8 );

// At this point we ensured the request comes from our user-mode module,

// so we can safely execute the logic of the hook handler

return 0;

}8. Advanced Features & Evasion

While the project’s core is data pointer hooking, the driver includes several low-level development and evasion techniques common in security software (and malware):

- Manual Import Resolution: Instead of relying on the standard Import Address Table (IAT), kernel functions (

PsLookupProcessByProcessId, etc.) are resolved at runtime. This makes static analysis more difficult. - String Obfuscation: All strings are XOR-encrypted to prevent them from being easily detected by static analysis tools.

- Manual CR3 Resolution: Capable of manually resolving a target process’s

CR3register (which points to its page table) by walking the PML4 structures, without using standard API attachments (KeStackAttachProcess) orEPROCESSlookups. - Anti-Stackwalking: Includes an evasion technique using

Asynchronous Procedure Calls - APCsand manipulating theKTHREADstructure to make stack tracing by detection tools more difficult, as some of them rely on queueing a kernel-mode APC to a suspicious thread to safely walk its call stack. - Physical Memory Access: Contains functionality to read directly from physical memory.

9. Security & Ethical Considerations

It is crucial to emphasize that this project is purely educational and for research purposes. The techniques shown are powerful and can be used for malicious purposes if they fall into the wrong hands.

- Kernel manipulation and bypassing protections (

CR0WP bit) are inherently risky. - Hooking kernel functions must be done with a deep understanding of the system to avoid BSODs and data corruption.

My goal with this type of project is to understand how these techniques work in order to, ultimately, design better defenses and security solutions.

10. Conclusion

This project was a turning point in my journey of learning Windows Internals. It forced me to think about C++ in a completely different way, to dive into low-level Microsoft documentation, and to debug in an environment where one error means a full system reboot.

It was a huge technical challenge, but the reward in knowledge was invaluable. I hope this detailed explanation helps you understand a little more about the fascinating (and dangerous) world of driver development and offensive/defensive kernel security.

11. Additional Resources

- Find the code described in this post here!

- SysInternals (Mark Russinovich)

- Windows Kernel-Mode Driver Architecture Design Guide

- Windows Client Docs

— Redaa.